FILM: THE VIETNAM WAR IN STONE’S ‘PLATOON’

Source: New York Times

By VINCENT CANBY

Published: December 19, 1986

NOTHING that Oliver Stone has done before – including ”Midnight Express,” for which he wrote the screenplay, and ”Salvador,” which he wrote and directed – is preparation for the singular achievement of his latest film, ”Platoon,” which is possibly the best work of any kind about the Vietnam War since Michael Herr’s vigorous and hallucinatory book ”Dispatches.”

For that matter, ”Platoon,” opening today at Loews New York Twin and Astor Plaza, is not like any other Vietnam film that’s yet been made -certainly not like those revisionist comic strips ”Rambo” and ”Missing in Action.” Nor does it have much in common with either Francis Coppola’s epic ”Apocalypse Now,” which ultimately turns into a romantic meditation on a mythical war, or Michael Cimino’s ”Deer Hunter,” which is more about the mind of the America that fought the war than the Vietnam War itself.

Much like Mr. Herr’s ”Dispatches,” this vivid, terse, exceptionally moving new film deals with the immediate experience of the fighting – that is, with the life of the infantryman, endured at ground level, in heat and muck, with fatigue and ants and with fear as a constant, even during the druggy hours back in the comparative safety of the base.

Life becomes very simple in such circumstances: ”we” are ”grunts” and ”they” are ”gooks.” That’s reason enough to kill or be killed. However, since the announced enemy remains invisible most of the time or, when visible, without particular character, an entire hierarchy of other, more comprehensible enemies emerges from the ranks of one’s comrades. Sanity is not a state of mind but a pair of dry socks. Objectives don’t have names. They’re numbered coordinates, drawn on a very small map from which the rest of the world has vanished.

Mr. Stone, himself a Vietnam vet, observes the war through the short focus of a single infantry platoon, fighting somewhere near the Cambodian border in 1967. It’s meant as praise to say the film appears to express itself with the same sort of economy that used to be employed in old, studio-made action movies -B-pictures in which characters are largely defined through what they do rather than what they say.

That’s only the impression, since the grunts in ”Platoon” do talk quite a lot, though for the most part, they don’t get too literary, nor do they explain too much. They are so exceedingly ordinary that they sometimes jump off the screen as if they were the originals for all the cliched types that have accumulated in all earlier war movies.

There’s the fellow who says with cheerful reason that, if you’re going to get killed in Vietnam, it’s better to get killed in the first couple of weeks. Otherwise, you just waste time worrying about it. There’s also the young, out-of-his-depth officer who does the best he can to talk his men’s language but, when he leaves their recreation hut, must say, as if exiting from the frat house, ”I gotta run. I’ll catch you guys later.”

At the center of the film is Chris Taylor, a new arrival who dropped out of college to enlist, a fact that strikes the rest of the platoon as profoundly comically irrational. Chris, beautifully played by Charlie Sheen, is about as close as ”Platoon” ever gets to a literary mouthpiece – he writes letters home to his grandmother, which we hear on the soundtrack, and in which he always – politely -sends regards to his mother and father.

Chris is idealized but without sentimentality. Part of him remains unknown and private, at least until the final minutes of the film, when Mr. Stone unfortunately feels called upon to have Chris say what has been far more effectively left unsaid.

The platoon’s most important figures are two NCO’s, each an exhausted, self-aware veteran of earlier Vietnam tours: the facially scarred Sergeant Barnes (Tom Berenger), who has somehow become committed to the war, which is all he has left, and Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe), whom the war has made as eerily gentle as Barnes is brutal. The two men, longtime friends, loathe each other.

Throughout the action of the film, the sergeants are fighting their own war for the loyalty of the men. It’s a measure of how well both roles are written and played that one comes to understand even the astonishing cruelty of Barnes and the almost saintly goodness of Elias. Each has gone over the edge.

Another measure of the film is the successful way Mr. Stone has managed to create narrative order in a film that, at heart, is a dramatization of mental, physical and moral chaos. ”Platoon” gives the impression at first of being only a little less aimless than the men, whose only interest is staying alive or, as Chris Taylor puts it, of remaining ”anonymous,” meaning safe.

Yet the tension builds and never lets up (until the anti-climactic final moments). Somewhere in the second half of the film, there’s a sequence of astonishing, harrowing impact that sort of ambles into a contemplation of how a My Lai massacre could have happened. It’s not easy to sit through, not only because it’s grisly but also because, all things considered, it’s so inevitable.

Mr. Stone’s control over his own screenplay is such that ”Platoon” seems to slide into and out of crucial scenes without ever losing its distant cool. He doesn’t telegraph emotions, nor does he stomp on them. The movie is a succession of found moments. It’s less like a work that’s been written than one that has been discovered, though, as we all probably know, screenplays aren’t delivered by storks. This one is a major piece of work, as full of passion as it is of redeeming, scary irony.

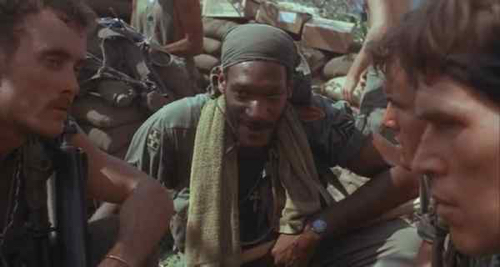

The members of the supporting cast are no less fine than the principal players, and no less effective, often, for being almost anonymous. Two particular standouts are Kevin Dillon, Matt’s younger brother, who has the flashy role of a certifiable, homicidal maniac with a baby face, and Keith David, who plays Mr. Sheen’s best friend, a black soldier who may be the only sane man in the platoon.

”Platoon” is a Vietnam film that honors its uneasy, complex, still haunted subject. BATTLEGROUND – PLATOON, written and directed by Oliver

Stone; director of photography, Robert Richardson; film editor, Claire Simpson; music by Georges Delerue; produced by Arnold Kopelson; released by Orion Pictures Corporation. At Loews Astor Plaza, Broadway and 44th Street; New York Twin, Second Avenue at 66th Street. Running time: 113 minutes. This film is rated R. Sergeant Barnes…Tom Berenger; Sergeant Elias…Willem Dafoe; Chris…Charlie Sheen; Big Harold…Forest Whitaker; Rhah…Francesco Quinn; Sergeant O’Neill…John C. McGinley; Sal…Richard Edson; Bunny…Kevin Dillon; Junior…Reggie Johnson; King…Keith David.

Tony Todd plays Warren.